My Experience in Istanbul, The Land of Antraman by Raquy

I was first exposed to the split hand technique in 2000 on a trip to Istanbul. I was hanging out backstage with some Turkish musicians and I saw the darbuka player doing crazy fast rolls. “What’s that?” I asked. He showed me: 1 3 1 3. I sat on the roof of my hotel for a week doing 1 3 1 3. Coming back to America, I began incorporating the 1 3 into my playing. “I’m doing the Turkish Split Hand Technique!”, I thought to myself. However, little did I know that there is so much more to this style than simply splitting the left hand into 1 and 3.

In 2009 I found myself making a living in NYC as a darbuka player with lots of work and many students, but in the inspiration department I was beginning to feel a little stuck and was craving a new challenge and a teacher.

I had a Turkish percussion CD called “Harem” that had beautiful, intricate compositions featuring the darbuka. “Who are these guys?” I used to wonder. I fantasized about going to Istanbul, finding the incredible drummers from that album and practicing with them.

I also started watching YouTube and witnessing the mind-blowing drumming coming out of Turkey. The way they played seemed inhuman. I found it impossible to decipher the patterns at those speeds. I could not imagine how many hours of practice it took to attain that level.

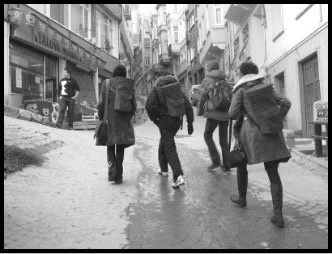

I decided that it was time to leave my ego in Brooklyn and make my first pilgrimage to learn from the master drummers in Istanbul. Accompanied by a group of my favorite students who happened to be all women, “The Magic Girls”, I set off for Istanbul. We rented an apartment in the heart of the “Tünel” music district of Istanbul and resolved to learn as much as we could.

You can imagine that as a group of beautiful foreign women drummers, we became instantly popular and soon got introduced to many of the musicians in Tünel. Someone recommended that we check out Bünyamin. I went to meet him in his studio near Taskim Square right behind the Aga Cami mosque on Istiklal. There were a bunch of percussionists hanging out there, practicing, drinking tea and smoking cigarettes.

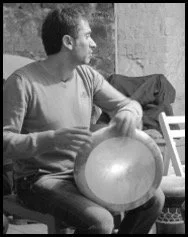

As soon as I saw Bünyamin play, I knew I had found my teacher. Bünyamin has been playing darbuka for 25 years. In addition to incredible speed and dexterity, Bünyamin plays every hit with a deep beauty I never before witnessed, putting him in a class above the rest.

Bünyamin immediately put me to work, correcting my hand position and giving me tons of exercises which I wrote down in my notebek[2]. The first lesson lasted about 5 hours! At the time I didn’t speak Turkish, so we had no common language, but with the help of my iPhone Turkish dictionary we were able to get by. Anyway, he said very little besides “yavash yavash” (slowly, slowly) for the first couple weeks.

I’ve had the honor of practicing with Bünyamin for over a decade and he blows my mind again and again. I’ve never seen anything quite like it – he channels incredible phrases one after the other as if it’s just coming through him. I copy him, write down as much as possible in my "notebek," and then together we organize the phrases into compositions.

At first I had private lessons with Bünyamin every two days and the other day he would teach the rest of the girls as a group class. In between lessons the girls and I would practice in our apartment, much to the chagrin of our neighbors who would complain by banging our window with their grocery baskets on a rope. “Whoops, got the basket, again, time to mute the drum! “

My lessons would go on for hours. Bünyamin wouldn’t work with me the whole time – he would sit with me for awhile, show me some patterns, and then go to the other room to smoke and drink chai while I worked on my own.

Bünyamin’s studio, it turned out, was a sort of headquarters for many of the greatest drummers in Istanbul. All of these guys who I’ve been hearing about and watching on You Tube would come by to smoke, drink very sweet chai and practice, and we would end up jamming together, everyone holding a rhythm and then taking turns soloing around the circle. And it turns out, Bünyamin was one of the original members of Harem, the Turkish Perucssion Group I was dreaming about! I manifested my fantasy!

What a humbling, challenging experience for me, getting to practice with drummers of such a high level! My biggest disadvantage has been speed and strength. Some of them have suggested that I need to eat meat in order to have the strength to play like them, but I’m determined to prove them wrong. (Just give me a couple more years!)

This style is incredibly addictive. You see everyone playing on the table, on their knees and on their friends when they don’t have a drum in their hand.

Many of the best players have a huge muscle on their left forearm from practicing so much. If you’re practicing correctly you’ll feel it in your left forearm.

In 2014 I opened my own Darbuka Ofis near Taksim Square in downtown Istanbul, right above Bünyamin’s Darbuka Ofis, how convenient!

I like to think of my Ofis as a gateway into this style. Darbuka players from all over the world come here to study with Bünyamin and I.

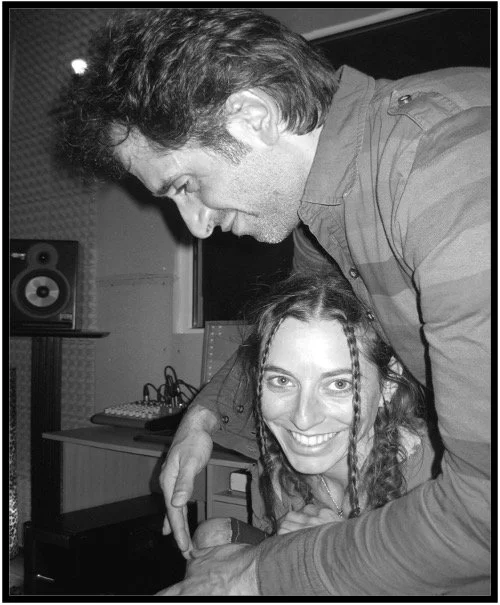

Bünyamin and I have created and recorded many duets and videos. You can hear most of the pieces in the duet album we released in 2017 called Darbuka Magic.

I also created DARBUKA SCHOOL, an online school where all of our teachings are presented.

Life at the Darbuka Ofis

I opened my my Darbuka Ofis in 2012. Since the it has become a popular destination for people flocking to Istanbul from across the globe to study the Turkish Split Hand Technique. Bünyamin and I give private lessons as well as offering intensive group seminars. As well as teaching, we practice together at the Ofis for many hours each day, and Turkish and foreign students join us for the nightly practice sessions to be part of this incredible drumming scene.

The Darbuka Ofis is located on Bekar Sokak, a side street off of the pedestrian walkway Istiklal, not far from Taksim Square. The picturesque old cobblestone street is lined with cafes, restaurants, food vendors, chai shops and music venues. From our Ofis we hear live darbuka and clarinet musicians strolling through the street, entertaining the restaurant goers for tips. When I look down onto the street, I see the people sitting outside with their mezes and glasses of raki, the food vendors carrying around trays of raw almonds on ice or fresh cucumbers with salt for a healthy late night snack. Downstairs, a clarinet player practices all day, and every time we pause, we hear the winding melodies drift up to our Ofis. Because it is common for music to continue into the wee hours on this lively street, there is no “curfew” for our music making.

When I studied classical music, I would go to the teacher once a week for a private lesson, and for the rest of the week, it was up to me to practice alone. In many Eastern cultures, taking lessons is more like a way of life where the lines between lessons, practice and playing for fun are nicely blurred.

At the Darbuka Ofis, in addition to the private lessons, the student is also invited to attend some of our practice sessions where Bünyamin and I, as well as other master drummers and students come together to practice. The more advanced players play on the clay Darbukas and the newer students play on the clay pot (ghatam). Some of the students find it enough of a challenge just to follow our rhythms and try clapping on the 1 of each measure.

Most of us sit on the floor. Bünyamin used to sit on a chair but in the last year he switched to sitting on the floor with his legs folded under him and the drum on the side. I also began sitting in full lotus position to play. Most of the others follow our example and sit on the floor, but we do have stools for those who aren’t comfortable on the floor.

When I practice with Bünyamin I always keep my “Dumbek Notebek” and a pen right next to me so that I will be ready to write down any new patterns or techniques that emerge. I do not trust myself to remember the patterns the next day, so I make sure to write down anything I might want to remember later.

A practice session is based around chosen meters. Our favorite meters are seven, nine and ten. Occasionally we play in 4 as well. In this participatory model, Bünyamin plays a rhythm and everyone joins in. He usually starts out quite simply but he keeps on “shifting gears,” getting more intricate and faster, culminating in a peak in which he climaxes and lands on the one. It is a beautiful moment when we all feel that together. Often celebrity drummers will surprise us and stop by, joining the practice sessions and bringing us new rhythms and ideas. Nobody is allowed to play louder than Bünyamin, who does not play very loud. A newcomer who plays too loud will be asked to play softer.

We go through several pots of chai every day. Most Turks drink black tea with sugar all day, but at my Darbuka Ofis I serve a special blend of hibiscus and cinnamon or sometimes fenugreek seed chai. The cinnamon makes it so sweet that even the Turks usually don’t need to add sugar. I also serve nuts and dried fruit – pistachios, hazelnuts almonds, dried figs, and apricots. Those snacks plus the chai can keep us drumming for hours without having to eat anything else!

Every couple of months we do week long seminars in the Ofis, and people from all over the world come for intensive lessons with Bünyamin and I. It is gratifying to see this style catching on and uniting people of different cultures. The international drummers who come to the Ofis often return to their country and teach locally, helping to disseminate this beautiful art form.